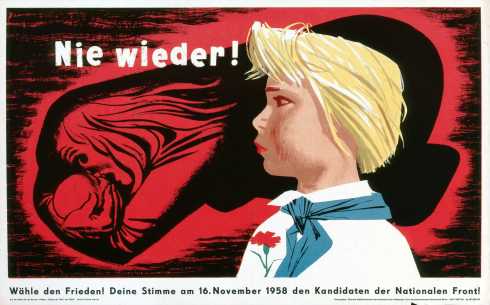

Never Again! East German National Front election poster 1958.

In 1968, East Germany went about adopting a constitution that would provide the legal basis for country’s state-socialist system. Rather than simply imposing this new document, as the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) could have easily done, it instead chose a more labour-intensive option: a mass national discussion followed by a plebiscite. Between February 2 and the vote on April 6, 1968 nearly a million events and meetings were held throughout the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to discuss the contents of the proposed constitution. Over the course of this Volksaussprache, the constitutional commission received more than 12,000 letters and post cards from East Germans, expressing their support, concerns, and criticisms.

Pro-Constitution rally at Humboldt University, East Berlin. April 5, 1968.

But wasn’t East Germany a dictatorship? What was the point of such activities when it was clear to all from the beginning that the new Socialist Constitution would become law if the SED wanted it to happen? Much of the political structure of the German Democratic Republic appears similarly strange in retrospect. Even before East Germany was officially founded in 1949, the SED was clearly the sole power due to the influence of its Soviet patrons. In spite of this fact, there were several other political parties such as the Christian Democrats and the Liberal Democrats who also held seats in the national parliament, the Volkskammer. Article 1 of the new constitution of 1968 made it official that the SED was the leading party of East Germany, yet there continued to be elections until 1989. What was the point exactly?

While from the perspective of today, parties, parliaments, and elections that aren’t part of a competitive political system seem absurd, but they served important functions. These institutions did serve to represent the views of constituents, but rather created venues to include and mobilize the population and to ritualized both their sense of belonging and the legitimacy of the SED.

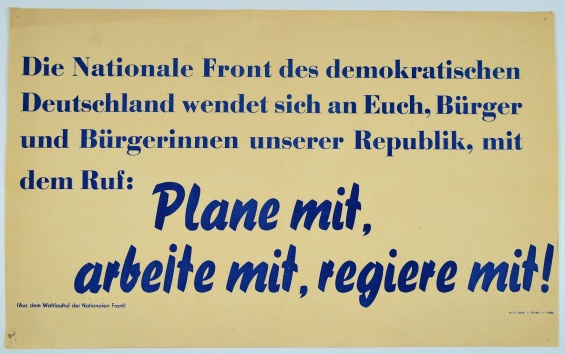

“The National Front of democratic Germany turns to you, citizens of our Republic, with the call: Plan together, work together, govern together!” 1958 East German election poster.

When the GDR was first formed in 1949, it was not officially run by the Socialist Unity Party, nor was it even ostensibly a socialist country. According to its leaders, it as an anti-fascist state run by the National Front: a collection of like-minded socialist and bourgeois parties committed to overcoming East Germany’s Nazi past. This National Front was led by the Socialist Unity Party (formed from the merger of the Social Democrats and the Communist Party in 1946) but also included several others.

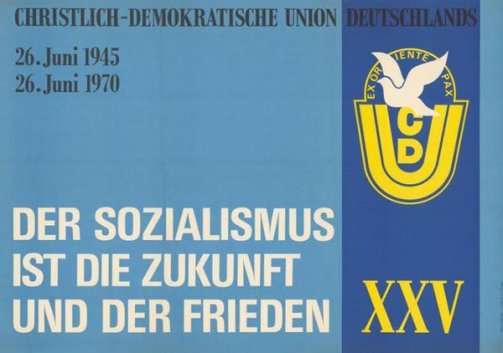

East German Christian Democratic party conference 1970 – Socialism is the Future and Peace

The Christian Democratic Party (CDU) and the Liberal Democrats (LDPD) formed organically in the post-war period, but were quickly tamed. CDU leader Jakob Kaiser was forced to resign by Soviet occupation authorities in 1947 and then made to emigrate to the West the following year. Arno Esch who served on the executive of the LDPD was arrested by the NKVD in 1949 for “counter-revolutionary activities” and executed in Lubyanka prison in 1951. With such examples, their successors discovered that following the lead of the SED or emigration to the West was a sound strategy for survival. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Foreign Minister of West Germany from 1974 to 1992, was one of those who began his political career in the East with the LDPD, before moving West in 1952 to join the Free Democrats of the FRG.

Why not simply shut down the parties altogether? Because they helped to integrate key parts of the East German population into the political system. The CDU helped to bring the Catholic population into the fold and the LDPD organized liberals and small business owners (private enterprise still existed on the margins of the GDR economy). Rather than write-off whole segments of the population that were not prepared to join the SED, these parties created spaces for ambitious people who wanted to collaborate with the system.

The SED along with the Soviet occupation authorities actually created other political parties, to appeal to otherwise under-represented groups. The Democratic Farmers’ Party of Germany was created in 1948 to bring in people from rural parts of the Soviet Zone (and dilute the influence of the CDU and LDPD). The National-Democratic Party of Germany was formed in the same year to provide a political home for middle-class former Nazis. In post-war Germany on both sides, there were plenty of former Nazis willing to conform to the new power structures if given a political home where they could do so.

Why would anyone join such parties? Membership in the parties gave you access to more resources and influence without forcing you to join the Socialist Unity Party. These Bloc Parties had their own headquarters and daily newspapers. As a member of one of these parties your requests and petitions had a better chance of being heard and acted upon by those in a position of real power. The top members of the parties also served in the Volkskammer and held important positions in the state apparatus. Georg Dertinger of CDU served as foreign minister from 1949-53 and Lothar Bolz of the NDPD succeeded him from 1953-65. Johannes Dieckmann of the LDPD was President of the Volkskammer from 1949-69 and Gerald Götting of the CDU succeeded him and serving until 1976. Even in the 1980s, when such positions were no longer available, the four bloc parties each still had more than one hundred thousand members, in comparison with the 2.2 million in the SED.

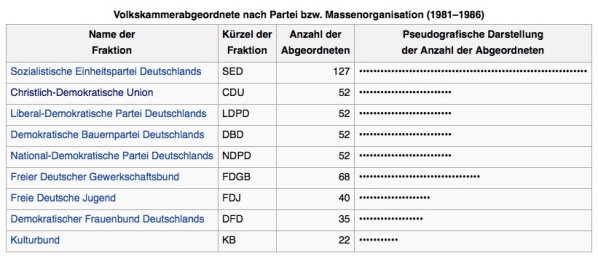

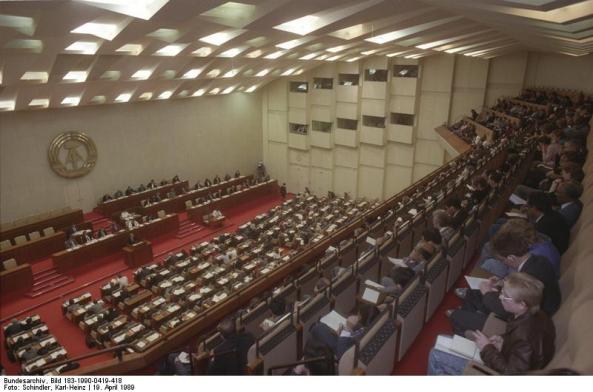

The Volkskammer was similarly a venue for displaying the unity of the various parts of the GDR. East Germany ran according to the principles of “democratic centralism” with the SED in charge of all substantial policy decisions as a Leninist “Party of the New Type.” The SED dominated State Council rather than the Volkskammer was responsible for formulating all laws and policies so the parliament served to symbolically ratify these choices. Representatives sitting in the parliament were not just from the various parties but also from the mass organizations created by the SED: the Free German Youth, the Free German Trade Union Federation, the Democratic Womens’ League and the Kulturbund (for intellectuals). Symbolically, the Volkskammer represented East Germany in all of its diversity, working together and acting in concert under the leadership of the SED. In discussions over laws and policies, each faction and representative was able to voice how plans would benefit their own constituents and the country as a whole. Before 1989, there was only one free vote: in 1972 the CDU was allowed to vote against the liberalization of abortion law. In all other cases, votes were unanimous as a signal of the unity of the people.

Distribution of seats in the East German Volkskammer 1981-1986

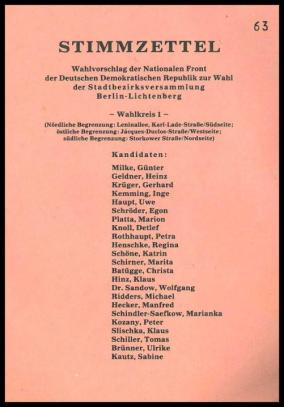

Elections took place every four to five years and while the National Front candidates received more than 99% of the vote every time, there was more to these events than mere propaganda. East Germans were given ballots with a list of the National Front candidates for their district. They had the choice to submit the ballot directly without changes to indicate their approval or to cross off specific names to show rejection. This all had to been done in public so rejections could lead to personal or profession repercussions. As a result, the vast majority approval did not have to be falsified as it was manufactured before hand through social and political pressure.

Interior of the Volkskammer located at the Palace of the Republic in East Berlin ADN-ZB/Schindler/19.4.89/

At the same time, the SED did not see universal turnout for these elections as guaranteed and had to work locally to ensure people actually came out to the polls. Complaints about consumer goods and housing conditions tended to spike prior to elections and local functionaries were under pressure to show diligence in solving these matters to keep the public happy. The SED worked in particular to cultivate the support or at least the silence of members of the clergy, sometimes in exchange for material support for a local church. The SED saw the procedure of the community coming out to vote as a crucial psychological tool in the affirmation of East Germany as Democratic Republic with the SED serving the needs of the people.

Music at a voting station in 1971 Volkskammer election

The new constitution of 1968 and its referendum combined all of these functions together. SED leader Walter Ulbricht saw the constitution as the symbolic confirmation that the GDR had progressed from an anti-fascist state to one of real existing socialism. In keeping with Marxist-Leninist ideology, the GDR was progressing on the path from the bourgeois stage of history towards the end point of history: communism. The new constitution explicitly confirmed the leading role of the SED, democratic centralism as the basis for the East German political system, and a partnership with the USSR as the bedrock of GDR foreign policy.

The vast number of meetings and discussions surrounding the adoption of the new constitution were meant to both educate the public and ensure their participation in the final vote. Objections and concerns were passed upwards to the SED’s leadership and responses were formulated so that they could be relayed by local functionaries. For example, when many complained about the absence of a right to strike talking points were developed with counter-arguments: functionaries explained that industrial action in a socialist country made no sense as the workers were already in control. This would be akin to West German press magnate Axel Springer striking against himself. During the constitutional discussions, East Germans were given comparative free reign in their criticisms, which were usually attributed to misinformation from West German television. In one meeting report I read in the archives, when one youth complained that the whole process was a foregone conclusion and pointless, his outburst was excused on the grounds that he was simply poorly educated during his military service.

Our “YES” to the socialist constitution of our GDR

While collective action was normally seen as prelude to conspiracy, in 1968 the Protestant and Catholic churches were able to organize a mass letter writing campaign (approximately half of the 12,000 the commission received) to demand more constitutional protections for the faithful. These letters demanded that the SED make space for Christian socialism in the GDR arguing that they were good and loyal socialists, but they would not be able to contribute to East German society if they were forced to adopt an alien atheistic worldview (Weltanschauung). In exchange for the SED accepting their Christianity, the letter writers were prepared to embrace socialism as an economic and political system. In the end, the SED added a second article on religious freedom as a concession to this mass response.

Whatever goodwill may have been generated by the process and the legitimacy it may have provided was largely erased soon afterwards. Warsaw Pact forces crushed the Prague Spring in August of that year (though without the participation of the East German military) leading many to see real-existing socialism as unreformable without drastic change. In 1974, the SED amended the constitution to remove sections on reunification. The appearance that the Constitution was a product of popular will was erased by its arbitrary alteration without any public consultation.

Local election ballot for Lichtenberg, East Berlin from May 7, 1989

In 1989, the electoral system that had for so long lain moribund rapidly came to life once the SED began to lose their grip on power. One of the problems facing the SED from the dissident movement was not their rejection of the system outright, but their demands to take part as active citizens. In a rejoinder to SED rejection of foreign criticism as illegitimate intervention in the affairs of a sovereign state, one East German activist adopted the slogan, “We have the right to intervene in our own affairs.” In May of that year, officials allowed for civic groups to monitor voting in local district elections for the first time. In spite of large numbers of rejections, the vote in favour of the National Front was still counted at more than 98%.

Local elections in East Berlin. May 7, 1989.

In the fall of 1989, the political bloc parties that had been quiet for so long forced out their leaders and became active once more. Three weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, on December 1, 1989 the Volkskammer voted to abolish the constitutionally guaranteed leading role of the SED. Soon after the SED transformed itself into the Party of Democratic Socialism – the predecessor to today’s Linke Partei. In elections held in March 1990, the new head of the Christian Democrats Lothar de Maizière became leader of the GDR government at the head of a coalition of conservative parties.

“Democracy now + here. No violence”

The bloc parties of East Germany were submerged into their Western counterparts and it is often forgotten that not only the SED successor party, Die Linke has roots in the German Democratic Republic. In 2008, the election of Stanislaw Tillich – who began his career with the East German CDU in 1987 – to the position of Minister President of Saxony brought the role of the other bloc parties back into public notice. Again in 2014, when the Social Democrats were criticized for joining in forming the government of Thuringia with Die Linke due to its GDR origins, they responded by calling for deeper investigation into the role of the CDU in the East German state.

Saxony Minister President Stanislaw Tillich with Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The existence of regular elections and political parties in East Germany does not disprove that the SED ran a dictatorial state. It does, however, complicate the simplistic view of the GDR as a totalitarian state that reduced its citizenry to a socially undifferentiated mass. The electoral system of the GDR is a window into the ideal of what the SED saw for East Germany – a united country of workers and peasants led by socialist party that represented the universal values of socialism. The bloc parties and elections in the GDR were propaganda, but they were more than just propaganda.

Why would the CDU, SPD etc in BRD allow their equivalents in DDR to effectively collaborate with the regime? I understand your argument that, to an extent, the East Germans were serious about engaging many sections of society in the political process, but ultimately it was still a fig leaf for dictatorship. Nicht wahr?

LikeLike

They didn’t have a choice in the matter. SPD in Western Zones protested the merger of the SPD and KPD in Soviet Zone but this didn’t make a difference. The CDU in the BRD was likewise powerless to stop creation or continuation of other Christian Democratic party

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Superfluous Answers to Necessary Questions | Max Hertzberg

Pingback: This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History – Imperial & Global Forum

Did not know the origins of Die Limke was GDR, not sure when they started to be more visible as my first arrival was 2000 and i then left Germany in 2005 and only came back in 2013, no recollection of them from my first time. Maybe more visible in BW than where I lived previously in rural Hessen.

LikeLike

The Linke was only founded in 2007 from a merger of the PDS, which was the direct SED successor party formed in 1990 and the WASG which was a left-wing faction that split from the SPD in 2005. In the early 2000s, the PDS had barely any support outside the former GDR so it’s not a surprise you didn’t see much of them.

LikeLike

Pingback: Η Ελληνοφρένεια και τα όρια της ελευθερίας της πληροφόρησης – προλετάριος

Pingback: 東德:建不同政黨,維穩良藥? - *CUP

Pingback: Lý do người Đông Đức thất bại – Chuông Rè